Though tenured faculty have some of the most demanding jobs at universities, their status has been an ongoing topic of debate in higher education, and their numbers are on the decline.

At the University of Minnesota, some faculty members and administrators say tenure has no demise in sight, as it’s necessary for academic freedom and quality work.

Still, others are skeptical that tenure status will stick around.

Universities typically build tenure into a faculty member’s contract, and it can provide the promise of higher pay and one of the highest forms of job security.

Faculty members work for years to receive the benefits tenure offers, and many times if they aren’t selected for tenure, they’ll consider leaving the institution.

“Being tenured means you have responsibilities and job security that are frankly in short supply in this country and in most countries,” tenured sociology professor David Pellow said. “It’s something that I see as a rarity in not only the labor force, but increasingly in academia.”

Finding a balance

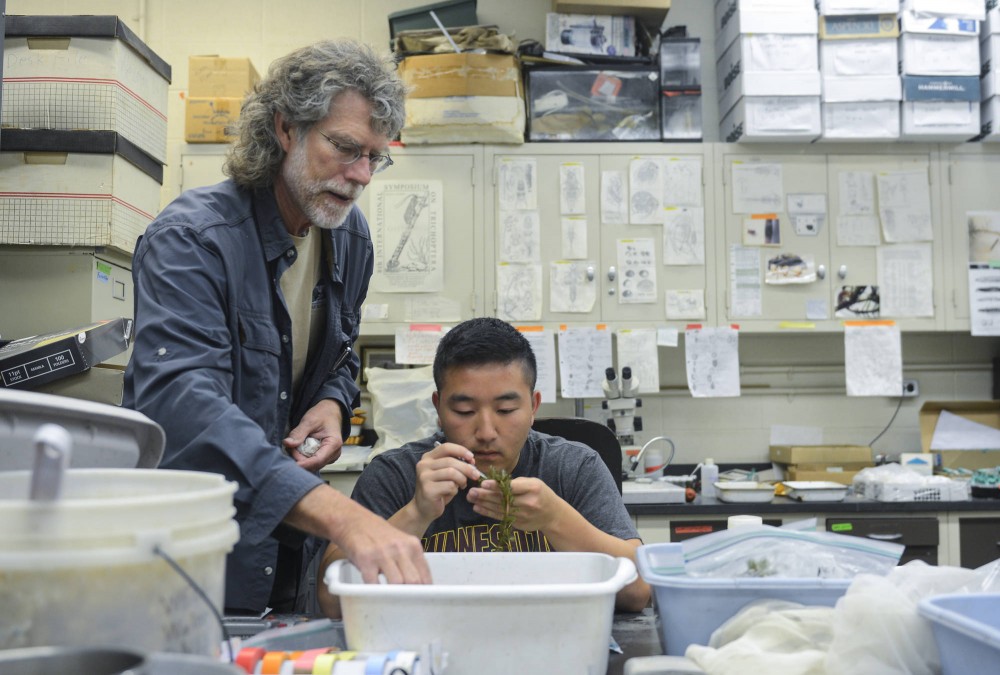

Fisheries, wildlife and conservation biology professor Raymond Newman has been a tenured faculty member at the University since 1997.

His position allows him to conduct research without having to consider the institution’s biases. He’s also able to teach what he feels is appropriate material, even if it clashes with the beliefs of University administrators.

“The underlying academic freedom idea is really the basis of being able to investigate questions where your science or scholarly inquiry leads you,” he said, “or similarly in teaching, being able to teach what [seem] to be the prevailing ideas.”

Those who hope to gain tenure status at the University, a research institution, have to find a balance between leading research in their field and being among the school’s top educators, and they must maintain that balance after receiving tenure.

Faculty Senate Vice Chair and tenured associate professor Eva von Dassow said the job of a tenured faculty member can encompass not only research and education, but also administration, governing and public engagement.

Sometimes, she said, faculty members have to make compromises in their work to excel in one area.

“Not all of us are equally good at all of the different aspects of our job,” she said. “In any given year or semester or week, any of us might do better or worse on one or another aspect.”

Pellow said many research universities evaluate their faculty on research first and teaching abilities second.

That system, he said, can create tension for faculty members in prioritizing between teaching and research.

“My philosophy is that a research university is a place where professors … are forced to really deal with that tension and it’s not easy,” Pellow said, “and that both the professors and students can suffer as a result.”

Still, Pellow said that in his experience, faculty members at the University work hard to meet the high standards set for them.

Council of Graduate Students member Keaton Miller is entering the job market as an academic this year. He said he thinks the best way to avoid sacrificing quality in a researcher or educator is to create a system that rewards both aspects of the job — a concern, he said, that expands to K-12 education as well.

“In academia … we have a pretty good way of measuring and rewarding good research output,” Miller said, “and I think that we’re struggling a little bit with measuring and rewarding good teaching at all levels.”

As part of a national discussion, some are advocating for two types of tenure, von Dassow said, one being the traditional tenure and one that would allow instructors who have less research to contribute to be retained by universities.

Von Dassow said those who have the freedom to do research in their fields are the best people to teach students about those topics. She said preserving quality education relies heavily upon tenure because it provides continuity to curriculum.

“If you take away the freedom that is guaranteed by tenure, or the prospect of tenure at least,” von Dassow said, “you take away the quality of educating.”

The tenure war

While some say that tenure is the key to preserving quality in higher education, others argue that it’s slowly being phased out and could ultimately become obsolete.

Tenured faculty members are among the highest-paid individuals at many universities. Pellow said that, combined with their job security, makes their presence at the University a burden for the administration.

“People who … have more job security may be more likely to speak out and speak up,” he said. “It’s much easier to control such people when they don’t have tenure.”

The number of contingent faculty members who aren’t eligible for tenure has been rising for the past few decades, said Gregory Scholtz, director of the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure, and Governance.

According to University policy, colleges can’t appoint more than 25 percent of their teaching faculty to a position without tenure opportunity.

In the late 1990s, von Dassow said, a regent tried to change the University’s relationship with faculty so they would be tenured to departments rather than the institution.

That method would allow the University to eliminate departments regardless of the status of faculty members within it, she said. Faculty members disapproved of the idea and successfully fought against it.

Pellow said he thinks the University, rather than outright eliminating tenure, is slowly phasing it out by hiring more adjunct and part-time faculty where tenured faculty once were — a decades-old trend in higher education.

But interim Vice Provost for Faculty and Academic Affairs Allen Levine said in an email interview that the declining trend at the University is due to factors like grants, enrollment numbers and the economy.

He said tenure cannot become obsolete at the University, adding that the institution has one of the strongest statements on academic freedom and tenure in the U.S.

The University is making no effort to decrease its number of tenured faculty, Levine said.

“The University of Minnesota is committed to hiring tenure-stream faculty members,” he said in the email. “Without the ability to offer tenure, the University would not be able to compete and attract some of the best researchers in world.”