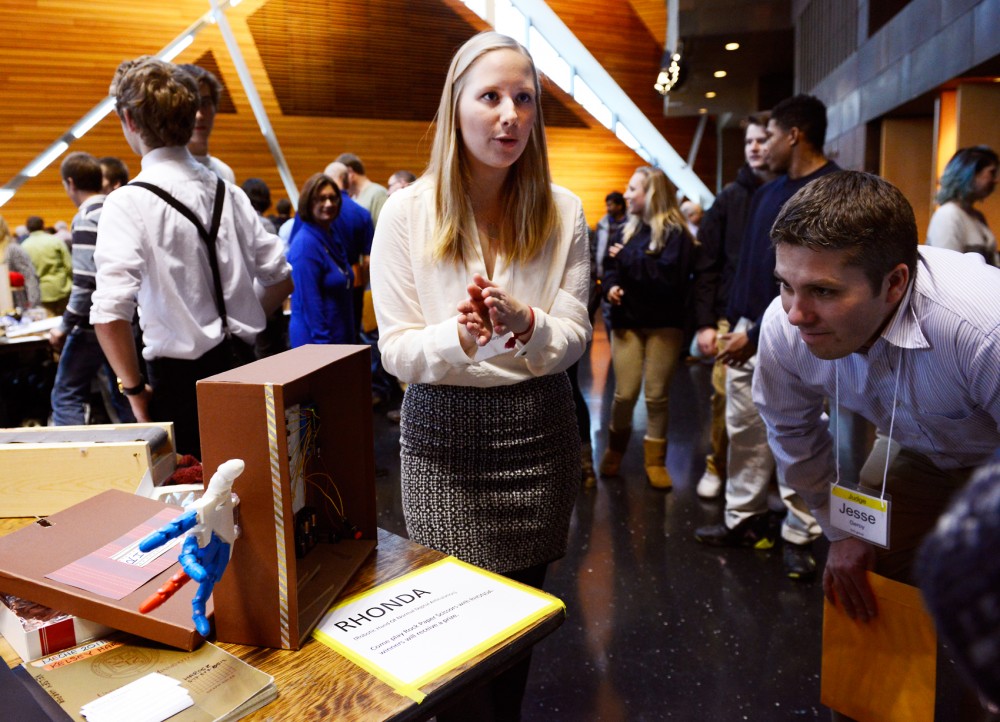

One of the 210 robots occupying McNamara Alumni Center on Monday sliced a pizza, while another dunked Oreos in a glass of milk.

University of Minnesota students presented the robots — which included s’more-roasting and light-saber-twirling machines, as part of an introductory mechanical engineering course. The 14th annual robot show attracted families and spectators as judges graded the students’ final projects.

The show originated in the early 2000s when mechanical engineering professor William Durfee decided to make the theory-based class more hands-on, assistant professor Tim Kowalewski said.

“The idea was, the very first class you take, we give you all the basic tools you need, and you’ve got to solve a realistic engineering problem,” he said.

Students are tasked with designing a robot that does “something interesting and useful” while spending less than $50, Kowalewski said.

“Students, when they’re done with this class, get an idea of what it’s like to be an engineer. And part of that is not knowing everything,” he said.

Ben Arcand, a third-year judge of the show, said each year he looks forward to the clever ways students’ robots solve problems.

Factors that make a robot stand out include aesthetic, complexity and how well the student constructs it, he said.

Many of the judges have ties to the industry or particular companies, said Arcand, who is the University’s Medical Devices Center assistant director and principle engineer at ArteMedics.

More than 400 mechanical engineering professionals attended the event this year, Kowalewski said.

Mechanical engineering junior Reed Johnson created a three-armed robot he calls “Trident,” which draws the Minnesota block “M.”

The arms attach to the top of a pen and guide it in forming the outline.

“I’ve always loved building things,” Johnson said. “[And] I love designing things and making them come to life.”

Kowalewski said Johnson’s robot was advanced well beyond the introductory level of the class.

Johnson used his own 3D printer to create the delta robot, a type of robot used by manufacturing companies, he said.

“[Johnson]’s got a 3D printer that he built in his house, and he’s used this 3D printer to build this amazing robot that impresses the instruction staff and all the faculty,” Kowalewski said.

Sophomore Setu Patel said he took an inventor’s approach to the project by making something that could be practical in his daily life.

Patel said he spent about four days working on his robot, which can sketch designs and take notes.

Patel said the building aspect came easy for him, but coding, a new concept he learned in the class, made the project more challenging.

“I might not be as strong in school; I’m not a straight ‘A’ student,” Patel said. “But this is what I’m good at.”

Being able to present his work to others and showing them how it works has been the most rewarding part, he said.

Sophomore Erika Beek designed a microcomputer-controlled circuit that flips pancakes using a series of three motors.

“When I was doing the assignment, I’ll admit I might’ve been a little bit hungry for pancakes,” she said.

Beek said she spent at least 40 to 50 hours of trial and error working on the robot.

“It’s kind of the first thing that I’ve ever done on my own,” Beek said. “It proves that I can do something in mechanical engineering.”